Georgetown Lutheran Church v. developer: an 1829 U.S. Supreme Court Case

By the early nineteenth century, Georgetown Lutheran Church was in disarray. The original log cabin church built in 1769 had fallen into disrepair, and regular services were no longer held.

There remained, however, a burying ground on the land that had been allocated to the Lutheran Church by Charles Beatty and George Frazier Hawkins in 1769. Grave markers for early members of the congregation were clearly visible, and the land had been fenced to keep animals away.

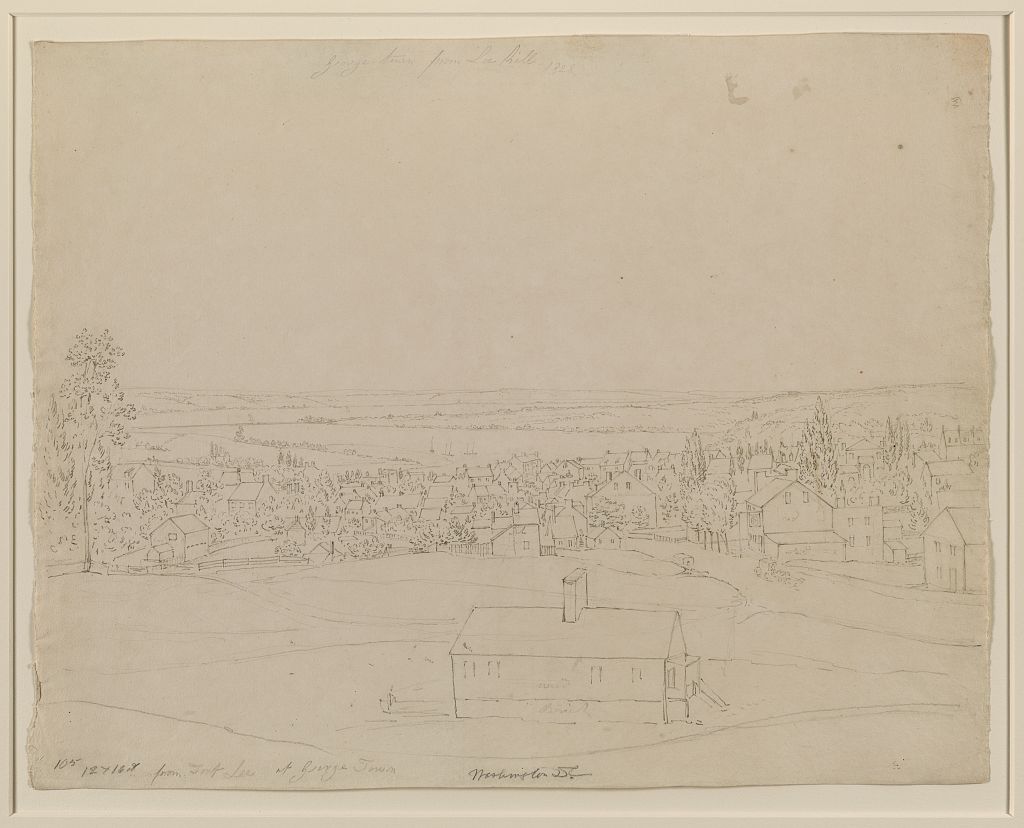

The heirs of Beatty and Hawkins saw in the derelict church building an opportunity to reclaim the land deeded to Georgetown Lutheran Church and use it to develop new, more lucrative, buildings. According to court documents, they entered the property and “threw down the fence and tombstones.” Georgetown had grown considerably since 1769, and was now more densely populated, with rowhouses sharing space on the streets with businesses and public buildings, as seen on the artist sketch below.

John Rubens Smith, Georgetown from Lee Hill From Fort Lee at Georgetown, 1828 (Library of Congress)

Although the church building had fallen down, there still existed a voluntary society of Lutherans, and they filed an injunction seeking to end the trespassing and resolve the dispute over the land title. The case eventually found its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where it is recorded as Beatty v. Kurtz, 27 U.S. 566 (1829).

The heirs of Beatty and Hawkins claimed that the 1769 deed to the Lutheran church was conditional, which would have terminated the title when the church fell down and was not replaced.

The Court found in favor of the Lutherans. Justice Joseph Story, writing the unanimous opinion of the Court, affirmed a perpetual injunction against the heirs of Beatty and Hawkins (the defendants).

George Peter Alexander Healy, Portrait of Justice Joseph Story

Here is a key extract from the decision:

“This is not the case of a mere private trespass; but a public nuisance, going to the irreparable injury of the Georgetown congregation of Lutherans. The property consecrated to their use by a perpetual servitude or easement, is to be taken from them; the sepulchres of the dead are to be violated; the feelings of religion, and the sentiment of natural affection of the kindred and friends of the deceased are to be wounded; and the memorials erected by piety or love, to the memory of the good, are to be removed so as to leave no trace of the last home of their ancestry to those who may visit the spot in future generations. It cannot be that such acts are to be redressed by the ordinary process of law. The remedy must be sought, if at all, in the protecting power of a court of chancery; operating by its injunction to preserve the repose of the ashes of the dead, and the religious sensibilities of the living.”

The Beatty v. Kurtz decision is considered a foundation of U.S. law regarding cemeteries and the status of human remains for several reasons.

-

It emphasizes the importance and special status of burying grounds.

-

It places burying grounds under the protection of a public court in the absence of an established church or ecclesiastical courts.

-

By referencing “irreparable injury,” it signals that the appropriate remedy to the “public nuisance”caused by the intrusion is equitable relief, not money damages.

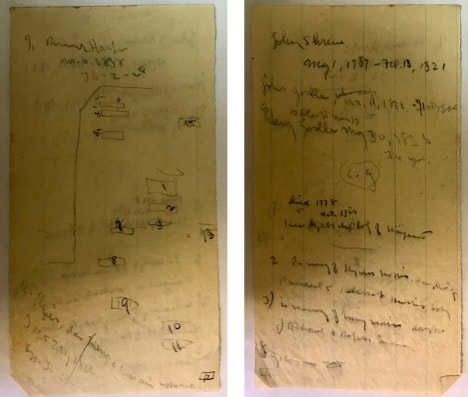

The Beatty v. Kurtz decision spurred a renewed energy in the Lutheran congregation, and a second sanctuary was built around 1835. The cemetery remained undisturbed until the construction of a parsonage on the land in 1920, which likely caused the graves to be removed. Some of the graves were still visible at the turn of the twentieth century, as can be seen on the pencil drawings below, drawn by Pastor Stanley Billheimer, GLC's pastor from 1894-1904.

Drawing of the grave markers and list of names still visible c. 1900